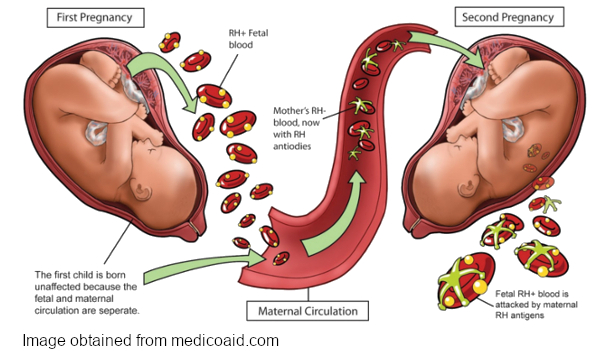

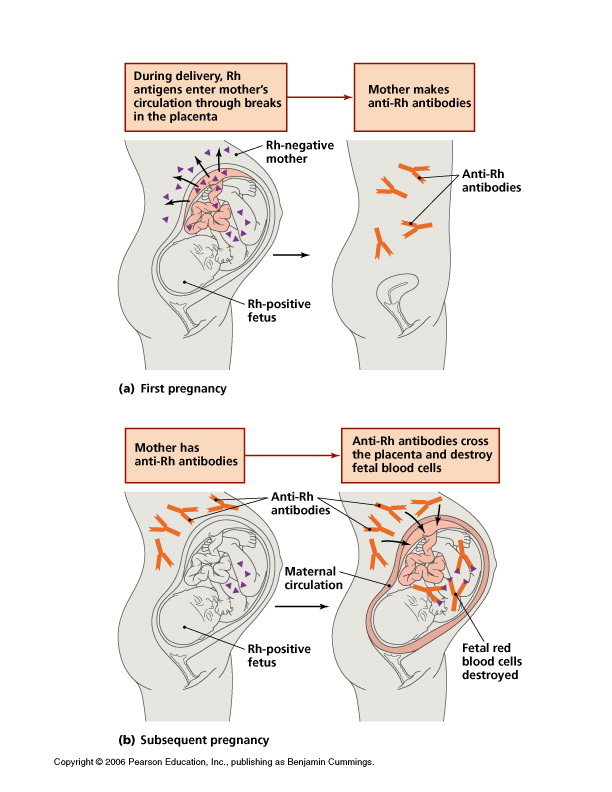

During pregnancy, there are a lot of ways the mother’s body protects and supports the baby. One way is to produce antibodies to ward off disease. But there are also risks that can affect the baby’s health. Since the baby inherits genes from both the father and the mother, its blood type is sometimes not compatible with the mother. This can lead to a condition known as hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn, or HDFN.

HDFN can develop when antibodies produced by the mother cross the placenta into the baby’s circulation and attach to the baby’s red cells, causing premature destruction of the red cells.

What is HDFN?

This condition was first described in the 17th century, but it was not understood until the 1930s. At that time, it was suggested that there was a factor that the baby and the father shared, that the mother was not compatible with. Babies that were affected were born with swelling, jaundice, and anemia, and sometimes were stillborn. This is a result of the mother being “sensitized” and creating antibodies to these foreign antigens. The antibodies attach to the antigens on the baby’s red cells, causing hemolysis.

Effects of HDFN

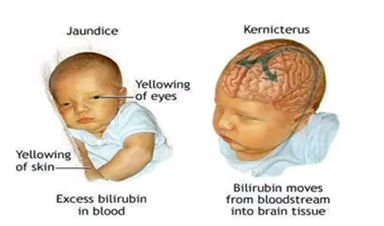

The destruction of the red cells can have many effects on the baby. Depending on the antibody and its strength, the symptoms may range from mild to severe. The baby may develop anemia or a low blood count. As red cells break down, they release heme, which is broken down into bilirubin. Excess bilirubin can make the skin appear yellow, also known as jaundice.

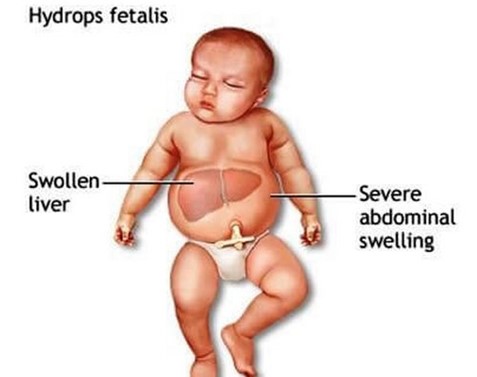

If the bilirubin gets too high, it may start depositing in the brain, causing brain damage, or kernicterus. As the number of red cells decreases, the baby will increase its efforts to make more cells. This can lead to enlargement of the liver and spleen, two organs that make red blood cells. Eventually, the heart can struggle to circulate blood and fluid buildup will occur. This can lead to edema and heart failure.

Diagnosis

One of the most important ways to avoid long-term effects for the baby is prompt recognition of the risk of HDFN. During pregnancy, the mother’s blood is tested for ABORh and red cell antibodies. If an antibody is detected, a titer will be done to determine its approximate strength. The titer will be repeated throughout the pregnancy to see if it gets stronger, or reaches a level considered harmful to the baby.

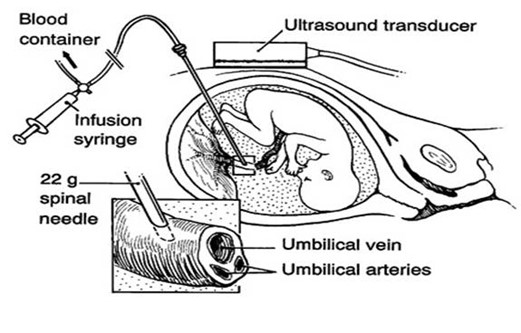

If the titer remains low, the baby may not be affected. If the titer increases, the baby may have the antigen and be affected by the mother’s antibody. Ultrasound may also be used to monitor the baby. Edema, circulation, and heartbeat can all be assessed. The velocity of blood flowing through the mid cerebral artery in the baby’s head can give an indication of the hemoglobin level of the baby. Tests for hemoglobin and bilirubin can be done from the umbilical cord, and other tests may be done on amniotic fluid, although both of these are invasive procedures.

Red cell antibodies that can cause HDFN include Rh antibodies such as anti-D, -E, -C, and -c, and anti-K. Next to anti-D, anti-K can cause some of the most severe cases of HDFN. Not only are the baby’s red cells affected, but also the progenitor cells. Even though the baby’s body tries to increase the production of red cells, it cannot because the immature cells that become red cells are also destroyed. Since the mother’s antibodies remain in circulation for several months after birth, the anemia can persist, and several transfusions may be needed.

Many mothers and babies have an ABO incompatibility. Mothers who are type O have anti-A and anti-B in their plasma. If they have a baby who is type A or B, they may be affected by the mother’s antibodies. However, in most cases, HDFN resulting from ABO incompatibility is mild.

Prevention

HDFN is one of the most important reasons to have good prenatal care. The most common type of HDFN in the past was when an Rh-negative mother was carrying an Rh-positive baby. They would frequently be sensitized and develop anti-D. Today, Rh-negative mothers receive Rh immune globulin during pregnancy and after delivery, and the rate of sensitization has dropped to less than 1%. Mothers can develop antibodies to any red cell antigen, so it cannot prevent all HDFN.

Treatment

Treatment is dependent on the severity of symptoms. The baby’s hemoglobin and bilirubin may be determined during the pregnancy. If the effects are severe, an intrauterine transfusion may be done. This is accomplished by putting a needle into the umbilical cord, called a “PUBS” procedure (percutaneous umbilical blood sampling). Blood can be collected and administered this way.

Depending on gestational age, an early delivery may be considered. Once delivered, the baby’s blood will be tested for ABORh, and a direct antiglobulin test (DAT). The DAT detects antibodies that are attached to the baby’s red cells. If the DAT is positive, an elution may be done. An elution disrupts the bonds attaching the antibody to the red cells and allows for the antibody to be identified.

Treatments after delivery may include exchange transfusion, where the baby’s blood is exchanged for blood lacking the antigen to the mother’s antibody, or a simple transfusion, where the baby receives a small amount of blood to increase the hemoglobin. If the symptoms are mild, a UV light may be used. The UV light helps the baby break down the excess bilirubin.