Many people, whether they are medical laboratory professionals or not, have heard of C. diff. infections (CDI). These infections cause inflammation of the colon (colitis) and severe diarrhea. CDIs occur when normal intestinal microflora is disrupted, which often happens after someone has been on antibiotics for an extended period of time.

What is C. diff.?

CDI is caused by the bacterium Clostridioides difficile (formerly known as Clostridium difficile prior to 2016). C. diff is an anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium that causes most antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) cases in the United States (nearly a half-million infections each year).

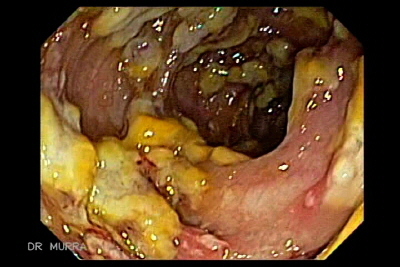

CDI can cause a condition known as pseudomembranous colitis (PMC), forming a lining of dead tissue, white blood cells, and fibrin over the inner surface of the inflamed colon.

Source: gastrointestinalatlas.com

C. diff. also produces toxins (toxin A and toxin B). Symptomatic patients can be negative for toxin A and positive for toxin B. Therefore, any testing for toxin typically looks for toxin B only, or the presence of both toxins A and B (but not toxin A alone). C. difficile toxin is detected in more than 95% of patients with pseudomembranous colitis, while only detected in 20-30% of individuals with AAD.

How do people become infected?

People with CDI pass C. diff. spores in their feces. Spores are formed as a defense mechanism by some bacteria and other organisms as a means of survival. Organisms that form spores are resistant to many disinfectants and antibiotics, and can survive on surfaces for months. Therefore, if anyone touches a contaminated surface and does not wash their hands before touching their face/mouth or any food products, they accidentally ingest the spores and infect themselves. In a hospital or long-term care facility, healthcare workers that do not follow proper handwashing and disinfection protocols may pass these infective spores to other patients.

What are the signs and symptoms of C.diff infection?

- Watery diarrhea ≥ three (3) times per day that lasts two (2) or more days. This may lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance and typically requires medical attention. Patients with watery diarrhea ≥ 6 times per day, which is very serious, require immediate medical attention.

- Fever

- Cramps/belly pain

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

Other diseases or conditions, in addition to PMN mentioned above, that can result from having CDI are:

- toxic megacolon,

- perforated colon,

- sepsis, and in rare instances,

- death

Infection vs. Colonization

Infection means that someone shows clinical symptoms of the disease and tests positive for the C. diff. organism or its toxin. These patients are considered to have true CDI.

Some people may have the C. diff. organism (or its toxin) present, yet show no clinical symptoms. This is called colonization and is actually more common than CDI.

What are the risk factors for C. diff infection?

- Antibiotic exposure over a prolonged period of time (especially with the following classifications of antibiotics – third/fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, clindamycin)

- 65+ years of age

- Having a severe underlying illness

- Having an immunocompromised status

- Having a previous CDI

- Having an extended stay in a hospital or personal care facility (increases the chance of being exposed to the bacteria from other infected patients)

- Having exploratory gastrointestinal procedures or gastrointestinal surgery

- Taking proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) that reduce stomach acids

- Having an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

How is C. diff. organism or toxin detected in the medical laboratory?

For any of the test methods listed below, it is very important the specimens for C. diff. organism or toxin are refrigerated (or specimen container is placed on ice) immediately after collection. C. diff. toxin is unstable and degrades at room temperature. The toxin may be undetectable within two hours after collection if it not refrigerated or left out at room temperature too long before testing. Specimens should remain refrigerated until being tested, and should immediately be placed back into the refrigerator after testing has been set up (in case the test needs to be run a second time).

Molecular Tests

When it comes to sensitivity and specificity, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is best for detecting the presence of toxin-producing C. difficile. However, PCR testing can still be positive in asymptomatic patients. Testing should only be done on symptomatic patients

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) increased in use between 2011 to 2017. This significantly reduced the number of CDIs in the United States, from nearly a half-million cases in 2011, to roughly 365,000 cases in 2017. The number of hospital-acquired infection (HAI) cases of CDI also decreased by 36%.

Detection of C. diff. Antigen

These are rapid tests that detect the presence of the C. diff antigen. Antigen testing alone is non-specific and should be done in combination with either toxin testing or PCR.

Detection of C. diff Toxin

- Enzyme immunoassays (EIA) are popular because they are same-day tests that are easy to perform and relatively inexpensive to run. These tests can detect toxin A, toxin B, or both toxins A and B. However, their sensitivity seems to be relatively low as compared to PCR.

- Tissue culture cytotoxicity assay detects only toxin B. While specific and sensitive, it is costly, requires special expertise to perform, and takes 24-48 hours for a final result. It is less sensitive than PCR.

Stool culture for C. diff.

While this may have once been the gold standard against which other test methods were compared, fecal cultures for C. diff. are labor-intensive with a slow turnaround time (48-96 hours). Also, non-toxigenic strains of C. diff. can yield false-positive results. So, any isolates identified as C. diff. should be tested for toxin production. This test method is not used as much anymore.

What is the treatment for C. diff.?

- Have the patient stop taking the antibiotic that likely caused the CDI.

- Shockingly, treat with different antibiotics, typically oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin.

- Repeat testing after treatment is not advised. Rather, look to see if the infected individual’s symptoms have improved. This is because patients can remain colonized with the bacteria, but not be symptomatic.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT) – Performed if other treatments do not work; helps normalize gut microflora and protect against C. diff. Fecal material from a healthy donor is transferred as a liquid mixture to the patient with CDI via:

– enema,

– upper endoscopy,

– colonoscopy, and

– some can be taken by mouth as a capsule.

Can people be infected with C. diff. more than once?

Yes. In fact, roughly 20-25% of patients that had one episode of CDI will have a recurrence of the illness. Of that group, approximately 45% will have a second recurrence, and of these patients, around 60% will experience further episodes of the disease. Most recurrences typically happen within one to eight (1-8) weeks after the previous infection.

Is there any way to prevent the spread of C. diff. infections?

C. diff. can be contagious if certain precautions and protocols are not followed. If the person with CDI is hospitalized or in a long-term care facility, taking these measures will help to keep spreading the infection to others.

- Even if CDI is only suspected and has not yet been confirmed, isolate the patient. If the patient is in the hospital or a long-term care facility, make sure they are in a private room ( if not possible, the patient may share a room with another patient with confirmed CDI).

- Handwashing. Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20-30 seconds (many people sing the happy birthday song twice as a way to make sure sufficient handwashing is achieved) and make sure to wash all areas of the hands (palm, fingers, between the fingers, under the nails, and the back of the hand).

- Thoroughly disinfect any surface or area that could potentially be contaminated with fecal material (door knobs/handles, sinks, bathtubs/showers, toilets). Use EPA-registered disinfectants that are also known to be sporicidal.

- Follow strict infection control protocols. Use isolation and contact precautions. Wear gloves and gowns when treating CDI patients (or those suspected of CDI). Most hand sanitizers do not kill C. diff. spores and sometimes handwashing alone may not be sufficient.

- Cautious use/prescribing of antibiotics. This is important for both patients and physicians. Patients – take your antibiotics as prescribed and do not stop taking them just because you feel better. Do not save antibiotics that have not been taken for another time when you feel sick. This does so much more harm than good! Physicians – don’t over-prescribe; if possible, wait for test/culture results before prescribing an antibiotic.

- If a patient is being transferred to another unit or facility, be sure to inform the new unit/facility of the patient’s CDI.

If the person with severe diarrhea or confirmed CDI is not hospitalized or in a long-term care facility, there are still measures that can be taken at home to prevent others in the household from being infected. These measures include 1) making sure everyone in the household sufficiently washes their hands with soap and water (especially after bathroom use and before eating), 2) limiting unnecessary visitors, 3) having the infected person use a different bathroom than others in the household, and 4) having the infected individual shower frequently, making sure they use soap.

Video from American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

Please check out these helpful infographics from the CDC regarding C. diff. and be sure to do your part to help in the diagnosis and prevention of CDI.